The Texas Tabernacle contains writings and photos about the people and history of the Palo Pinto River and the Leon River Country, Eastland, Palo Pinto and Stephens County, maybe old friends and detours that will likely occur along the way. I like to look for the old things...events that happened, or maybe should have. Listen to what they have to say.

Everything Matters

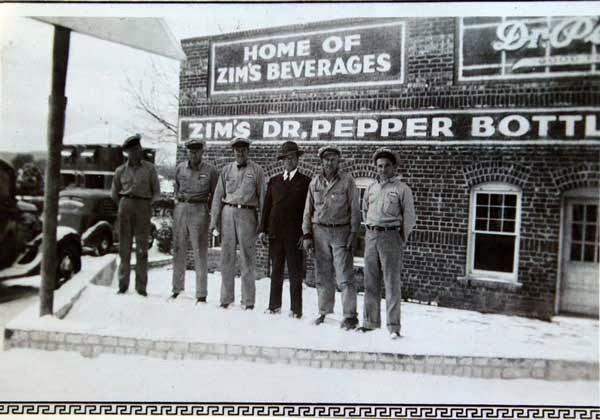

Zim's Bottling of Strawn

Monday, December 30, 2013

Friday, December 27, 2013

Wednesday, December 25, 2013

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Dodson Prairie Dances Tie Old Country to new

Dodson Prairie Dances

Tie Old Country to New

There’s a

scene in the movie “Titanic” about the fabled luxury ship’s fateful date with

destiny. The elderly woman in the film tells the story of her own voyage that

tragic night. She looks off across the waves many decades later, visions of a luxurious

whirling ballroom filled with dancing couples coming brightly back into view

inside her memory, inside her words. She makes us see it too. We are

transported.

I met with 95-years-young Lenora

Teichman Boyd last week. I like it when someone I’m interviewing says, “I can

only tell you what happened up until the 1940s.”

I’m wanting to learn about the monthly

Dodson Prairie dances, held about six miles west of Palo Pinto, the town. They

started just after 1910. Lenora is home from the hospital, from rehab after

back surgery to relieve constant pain. She’s sitting in a recliner, enjoying

the unseasonably warm December day. I pull up a chair.

“They had

the dances right out there.” She’s pointing out the window south and a little

east behind this house. The closest public building that direction is in Strawn

or maybe Mingus many miles away. But Lenora sees the old dance hall just

outside, about fifty yards away. She starts talking, teaching. She makes me see

it too.

Dodson Prairie really was in 1900 –

a prairie, I mean. There might be an occasional small stand of oaks out there,

she told me. Mostly one saw grass, as high as a horse’s belly. The flat prairie

is today covered in cedar and mesquite, flat earth loping west until the ground

erupts skyward into mountains, cleaved in two by Metcalf Gap. Lenora told me

that those early farmers would burn their fields back each year, to invite

fresh grass in the spring. The Comanche did the same, during their turn on this

land.

Dodson Prairie was and is a German

settlement. Folks worked hard, mostly farming, raising stock. Lenora’s Teichmann

Family arrived in 1900 from the Schulenberg-Weimar area (before that, from Germany in

1868, landing at Galveston ).

They’ve been hard at it in Palo

Pinto County

Once a

month area families gave a dance, a get together. There was a public wagon road

when this all got started, leading in from the west. That road is gone, though Teichmann Road

remains. Lenora keeps talking.

It’s a black dark Saturday night on

the Texas

prairie. Coal oil lamps paint pale orange light onto the dusty ground outside

Dutch Hall’s double doors. Saddled horses and mules are tied outside. The creak

of wagons pulled by teams approach from the west, puncturing the stark silence

of this bone cold December. Kids hop out and meet their friends, promise moms

they’ll stay close, then run off to play. “There was a bed in one corner of the

hall,” Lenora told me, “where babies could sleep.”

Dutch Hall was a tall community

building made of overlapping frame lumber. It might’ve been 30 by 50 feet,

though lonely brown foundation stones and a few wooden pilings are all that

remain. Dutch Hall was used for dances, lodge meetings, and other community

get-togethers. Night school for adults happened here. People came from all over

for those Dodson Prairie dances – from Thurber, Mingus, Gordon, Palo Pinto, even

the country across the Gap west toward Caddo.

We start to hear painfully brittle

sounds inside the wood-heated hall – trumpets, sousaphones, a bass drum, and fiddle

strings all looking inside the growing cacophony for a key they can all agree

on. Finally, the band starts playing and the silent prairie comes to life with the

joyous dancing, stomping and hand-clapping of hard-working farm families,

taking a break from their tough frontier.

Cap Foreman yells loud across the

heads of couples circling the floor. A square dance is called, couples circle

up, his loud voice centers all:

Meet your partner and meet her with a smile,

Once and a half, and go hog wild.

Treat ‘em all alike,

if it takes all night.

Married couples and still-shopping

young singles answer his call, with doe-see-does, and promenade rights. That

morning’s broken plow and the calf that ran away fade in importance to these

farmers and their wives.

Lenora’s father C. A. “Charlie”

Teichmann led the Dodson Prairie Band. He taught friends and relatives to play

brass instruments, and in one case a drum. At midnight , the wooden dance floor is cleared and large

tables are spread deep with fine native foods prepared by the Prairie’s

Germanic mothers and maidens. Families gather into Community here, from the

oldest great grandmothers to the youngest newborns, rock fences built to keep

in cattle, not to keep people out.

Dodson Prairie families were in

many cases only one generation removed from their European homelands. The Herman

Riebe family came here along with Joseph and Carl Teichmann, then the

Ankenbauers, Bergers, Beyers, Dreitners, Holubs, Kainer, Kaspers, Nowaks,

Popps, Schlinders, Telchiks, Thiels, and others.

One time “wild cowboys” interrupted the dance’s

fun after one too many snort from the bottle. Poor planning on their part became

apparent as lawmen were in attendance. The offenders were congratulated, then handcuffed

to oak trees outside until morning. As the years progressed, fiddles, guitars

and banjos replaced the brass-centric nature of Teichmann’s original Dodson

Prairie Band.

I asked Lenora about moonshine,

knowing it flowed liberally (I’m sorry, “freely”) to the south of here. “There

was no moonshine,” she tells me, and I believe her. “Well, there might have

been wine,” she finally admitted, these being upstanding Germans after all. I’d

been told elsewhere that no one partook inside. During breaks men might wander

outside for some light inebriation, I mean conversation. Many of these German

families had their own small vineyards at home, home grown mixed with wild

grapes from Lake Creek thickets down the hill. Do the math.

When the dances were over late on

star-speckled nights, Lenora’s family would walk through the dark about a

quarter mile to their home. Lenora remembers being carried. She couldn’t have

been more than three. Lenora remembers.

“Was

downtown Dodson Prairie right here back then?”

“No, it was

spread out. St. Boniface was to our south. The first schoolhouse to the south

of that, then the new schoolhouse was built north of the church. Over toward Highway

180 there was a cotton gin, west side of the road. Past that fell the store, the

post office inside. The Poseidon post office. And a filling station. The county

farm (poor farm) on the east, but that came later.”

The Teichman

Family (the second “N” dropped through the years) came from Austria and Germany to Galveston , then to central

Texas . They

must’ve scored down there, because they bought two full sections of land when

they reached this prairie. They paid between $2.50 and $4 an acre.

“Why did

they buy here?” I asked.

“Because it

was for sale,” Lenora answers.

It might have been because the

black soil at Dodson Prairie mirrors that found where the Teichmans farmed down

south, her son Charlie later tells me. Clearing these wide fields of rock, they

built stacked, drift rock fences by hand. The two fences I saw to the southeast

were two to three feet thick. A vintage photo shows another farther east rising

in height above a horse’s head.

Dances

moved to the “new” schoolhouse around 1950s. They occurred off and on there until

four or five years ago. The bands finally got too expensive.

When Lenora

was born in 1915 Woodrow Wilson was president. The Ranger oil boom was still

two years in the future. Dodson Prairie was a thriving, peopled settlement.

Back to

that German factor I mentioned earlier. Son Charlie and his friend Ann kindly loaded

me in their pickup to show me around the Prairie. I’d made a quick tour before,

not finding a lot. I wasn’t looking close enough.

Though

their early houses were mere box houses (no internal framing), both original

Teichman brother’s homes are still standing. From around 1900. One is being

lived in, standing in proud testimony to the hard labor and attention to

quality that these men and women nailed into place. The old school house, the

new school, several thick rock walls, the church, and several county poor farm

buildings are all standing. Those Germans built straight and true, though their

local population continues to wane.

Teichmann

and Schoolhouse Roads are two of the few roads in this area one can still

travel down and read many of the same family names that settled that land 100

years ago. This too, is changing. If you stand respectfully in a quiet spot out

Dodson Prairie way, I have to believe the old dance is still being held.

Couples twirl, long lost love still beating hard and true. Invisible dance

floors and midnight dance callers

invite the distant past into the prayed-for future. If you stand quietly. If

you believe.

Special thanks to Lenora Teichman Boyd,

Charlie Boyd, Ann Mixon and Gloria Holub. Jeff may be reached at jdclark3312@aol.com.

SUGGESTED CAPTIONS

PHOTO ONE . The

original Dodson Prairie Band members standing in front of Dutch Hall, circa.

1910.

PHOTO TWO. One of the two Dodson Prairie Homes of the

Teichmann brothers. This home was built in 1900, and is still lived in today.

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Visiting Grant Town Grandparents,

The 1930s Road from Seguin

(This story was written by Louis Scopel,

recalling childhood trips to Grant Town. Grant Town was a “suburb” of Thurber,

located just to the west, northwest. Many structures remain.)

“Travel from Seguin to Mingus was a trip attempted usually

not more than twice a year for reasons mentioned below. The distance was 245

miles on primarily on US 281, usually a highway in good condition. The trip

usually took from five to eight hours depending on stops etc. Most of our trips

were in a 1936 Plymouth

4 door. US 281, was wide enough for two cars and was pretty mundane on most

occasions. Plenty wide as you seldom met another vehicle every thirty minutes,

or at least, so it seemed. Once we left New

Braunfels , the next stop light was in Stephenville.

The 1936 Plymouth

diligently purred along with an under dash radio keeping dad aware of the

latest baseball scores.

We normally left when dad closed

down the poultry processing plant for the weekend and he took a quick bath – he

smelled better then. By then Mom had items packed and ready to go. Mom knew how

long these trips were as she packed plenty of provisions! There was the thermos

of coffee but containers of cookies, several cakes for Gi Gi and John Franks.

And there would be another bag of fruit and sandwiches. She seemed to believe

we might get stranded somewhere sometime. Anyway we would soon be purring along

after leaving civilization in New

Braunfels or so it seemed with our head lights piercing

the darkness. In later years I compared them to two candles!

When traveling in colder weather

our heating system worked great—three of us in the front seat with a blanket

amply dusted with crumbs, tucked across our laps. On one trip, as we approached

Marble Falls Marble

Falls

So we continued and as luck would

have it, there was a Texaco station open, and the young man was accommodating

enough. Yes, they did have a part time mechanic but he had went home for the

week end, however, with a bit of prodding he agreed to come in and look at the

Plymouth’s charging system. We agreed this was better than on the side of the

highway – we had food and a rest room. After arriving, the mechanic determined

it was the generator but questioned where do you locate one at this time of the

night on a weekend? Amazingly our mechanic located one, left and came back with

it under his arm. In short order the generator was ‘ginning’ again and the

lights were comparable to two candles once more.

Our trusty Plymouth would usually

rattle across the cattle guard in Grant Town between 10 and midnight waking everyone and

announcing our arrival – and time to eat and catch up on news. If my aunt Pauline was there, there would be

dishes and bowls of fudge and divinity etc.

{When Thurber shut down many people moved

out to Grant Town. "My mother and grandparents came to Thurber from Noted historian Leo Bielinski has written about Grant Town, and shares:

“Jimmy Grant opened a saloon just outside the city limits

of the Texas & Pacific Coal and Oil Company-owned Thurber. His saloon was

frequented by miners who could talk freely about unionization without fear of

company intimidation. Some immigrant Thurber miners moved out of Thurber to

Grant Town to own homes and small businesses. The area became known as Grant's Town,

shortened to Grant Town.”

"Today it is part of Mingus, but the locals still

refer to it as Grant Town. During Prohibition, there was bootlegging in Grant

Town, and after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, several honky tonks opened

up.”

"Johnny Biondini, Louis Scopel's uncle, summed

up the family's move from Thurber to Grant Town after the coal mines shut down

in Thurber: 'In Thurber we had all the modern conveniences like running water,

gas heat and electricity. But when we moved to Grant Town, just a quarter mile

away, we had to adjust to coal oil lamps, well water and wood stoves. There are

just a few left who lived in Grant Town before WWII."

“Thurber had a barbed wire fence around it to keep

Thurberites buying in the company store. Jimmy Grant's saloon was just outside

this fence. The immigrant Italians made up a fourth of Thurber's population,

but the company store did not stock the different salamis, cheeses, olive oils

etc. (which the Italians wanted). So in addition to Grant's saloon, there were

several Italians who set up small combination grocery store/saloons in Grant's

Town, just outside of the barbed wire fence to cater to the Italians on Thurber's

nearby Italian Hill: Sealfi, Ronchetti, Mezzano, Corona, Castaldo and Raffaele

[and others].”

"There were several prominent bootleggers in

Grant Town during the Prohibition era. Not just Italians, but all nationalities

were involved in bootlegging. When the mines began shutting down in the 1920s,

bootlegging was a way of surviving and had none of the Chicago style gangsterism. There was little

stigma if you bootlegged. The nearby Ranger Oil Boom was profitable for the

bootleggers."

Sunday, December 15, 2013

Saturday, December 14, 2013

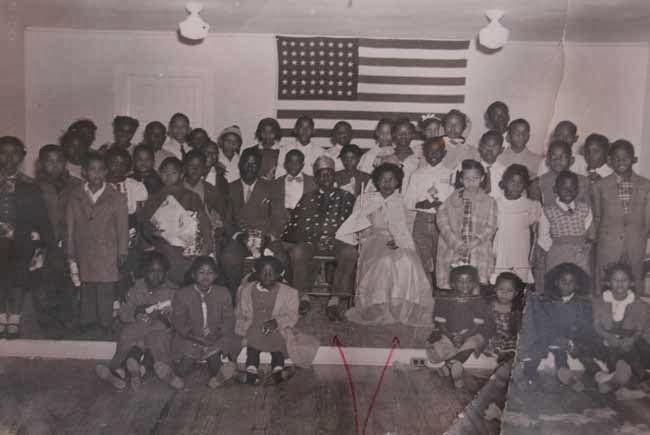

Weatherford, Texas Black School

Black Mount Pleasant School Forges

Two Communities Into One

Race riots may be coming to Weatherford. That was the talk around town. Images of angry police dogs, fire hoses and bloodied protestors across the Deep South paraded across Parker County TV sets in the early 1960s. Some feared a repeat performance here.

When Weatherford schools opened that first 1963 day of integration, all was quiet. The reasons are both simple, and complex.

Our mystery begins in church. Two years after the Civil War ended, blacks organized the Prince Memorial Christian Methodist Episcopal Church on Oak Street. This oldest “still in business” church in Weatherford was named after the Rev. A. Bartlett “Bart” Prince, its first elder (as is Prince Street, near the first black public school). The church’s building went up in 1871, and was modified in 1912.

The “CME” sign in front meant “Colored Methodist Episcopal” until the 1960s, when it changed to Christian Methodist Church. It’s believed to be the second oldest CME church in the nation. There’s no Texas Historical Marker here. Within this pioneer church’s walls, black students received their first education, until the county built them a schoolhouse. Smythe’s 1877 “Historical Sketch of Parker County” lists thirty-seven county schools that year, each tied to a geographic “community”, save one: School No. 33 – The Weatherford Colored School.

Seymour Simpkins taught thirty-nine “colored” students. Prince Memorial pillars Willis Pickard, Rev. Henry Johnson and Rev. Prince served as trustees. The “Colored School” gets mentioned in the newspaper off and on down through the years. In 1887, land just south of West Oak and west of Prince was purchased for $200, its schoolhouse built in 1917.

A brick school house replaced that structure in 1927. Today that forgotten brick schoolhouse stands proudly among the weeds. The September 8, 1933 Weatherford Democrat lists five ward schools that year, plus the “Colored School”. Tillie Woods was principal and Ella Varnel was the teacher.

The “Colored School” taught Cub Young, who pitched against Satchell Paige in the Negro Baseball League. Weatherford’s Negro League team played where Weatherford High School is now.

Within this pioneer

church’s walls, black students received their first education, until the county

built them a schoolhouse. Smythe’s 1877 “Historical Sketch of Parker County” lists

thirty-seven county schools that year, each tied to a geographic “community”,

save one: School No. 33 – The Weatherford Colored School. Seymour Simpkins

taught thirty-nine “colored” students. Prince Memorial pillars Willis Pickard,

Rev. Henry Johnson and Rev. Prince served as trustees.

The “Colored School

The September 8, 19 33 Weatherford Democrat lists five ward

schools that year, plus the “Colored

School Colored School Weatherford High School

Leonard Smith

entered first grade at Mount Pleasant

in 1939, three years after it was renamed the Mount Pleasant School

Most black

students walked to Mount Pleasant

from four Weatherford neighborhoods – The Flat (First Monday Trade Day Grounds

area), The Hill (West Oak Street

area), Sand Town Cherry

Park

Black and white

kids played baseball together, had rock fights, and cut up like children still

do. Raymond George and some of his white friends walked to school together in

the late 1940s. When they reached the Stanley School

“That’s just the

way it was,” he said.

Raymond remembers

there being about fifty students, though that number swelled when migratory

families came to town with the railroad or picking cotton. Raymond’s teachers (1946-1953)

included Ella Varnell, Lucille Rucker and Mrs. Roddy.

“Lucille Rucker

built the foundation beneath those black kids’ sense of respect,” Raymond said,

“respect for others and for themselves.” Not only was she a good teacher, she

was highly regarded by whites and blacks alike. Rucker made the boys play out

back and the girls play out front during recess. “She taught us to treat the

girls like ladies. Because of her, my generation of students stayed married,

kept one job our whole lives, and successfully retired from those same jobs.”

Still, when Mount Pleasant

closed, Mrs. Rucker was forced to do odd jobs to survive. “She wasn’t taken

care of,” he reflected sadly.

Wilson Hall was

added to the northwest edge of the Mount

Pleasant campus around 1944. Named after Superintendent

Leonard B. Wilson, it was a barracks-like building used for classes and

assemblies, with a stage on its west side.

Each large

classroom had wood floors and large windows along two walls. One can see

daylight looking up through fourteen foot ceilings to the sky. “These

classrooms were filled with little desks,” Charlie told me. “There were kids

everywhere.”

“Every morning all

the kids would walk out here, to the flag pole,” he said. “Say their Pledge of

Allegiance and sing a patriotic song.” The flag pole base remains. He showed me

where the swings were, the slide, the concrete front porch to Wilson Hall. “We

had more fun than you can shake a stick at.”

The schoolhouse road

entered from Prince Street ,

rising up the hill then circling the school. The old schoolhouse sits on

private property, contiguous to Love

Street Park

This was a time of

separate white and black drinking fountains in our city. Blacks couldn’t enter

white restaurants (unless they worked there) or attend most theaters. Blacks

could buy Texas Theater tickets, as long as they sat in the balcony. Raymond

remembers walking through the Texas Café to the kitchen out back as a little

boy, wanting to spin the bar stools around. He couldn’t since the place was whites

only.

Weatherford had black

churches, a black tabernacle, and a two-story black Masonic Lodge on Fort Worth Highway, east

of the courthouse. There were few black businesses.

If black students

aspired to go to high school, they were on their own. Raymond and Leonard went

to Fort Worth ’s

I. M. Terrell High School. Most of these kids didn’t have bikes, much less cars

to make the thirty-one mile journey each way.

Raymond’s dad John

Lorenzo “J. L.” George stepped up between 1953 – 1963. He left his upholstery

shop twice a day to drive black students to Cowtown in his Ford station wagon at

his own expense. Local businessmen later chipped in to buy gas. When J. L’s car

got too crowded, a bus was finally supplied. J. L. spent five hours a day toting

school kids, losing this time at his store.

Mitchell Rucker

was another pillar of the black community here, born in 1899. “He was respected

by the white community,” Raymond told me, “but held at a distance.” In the white

community, Rucker was employed at the M & F Bank as a janitor. In the black

community, he was superintendent at Prince Memorial for over fifty years, taught

classes to Senior Citizens for the WPA in 1944, taught soldiers at Camp Wolters Texas

College Tyler for forty years.

Rucker was one of the main conduits between Weatherford’s white and black

communities.

“Pappa Ike”

Simmons was another black leader. He attended school at Prince Memorial, before

Mount Pleasant

was built. “Pappa Ike was more of a politician – he knew everybody, running

that mouth 100 miles an hour,” Charlie told me. Ike and brother “Uncle Charlie

Simmons” each raised families off shining shoes at the Palace or Texas theaters and at

barber shops.

Many prominent white

families had black nannies, butlers, and groundskeepers. There was a parallel

but unseen black society here, one from which trusted black men like Rucker,

Pappa Ike and J. L. George could communicate informally with the white

establishment.

Equally important,

several white leaders reached out to the black community – Jack Borden, Borden

Seaberry, the Cotton Family, and James and Dorothy Doss, among a few others. Respected

whites and blacks interacted, albeit at a distance. Though not treated equally

by any means, attacking one group would’ve meant attacking their own.

Mary Kemp

remembers when the integration meetings took place in the third floor study

hall of the old Weatherford

High School

Charlie Simmons

was one of the first black students at Weatherford High School Mount Pleasant ’s

teachers and black leaders. “It was a simple transition,” he said. “Nothing

happened.”

This would be

another “happily ever after” Weatherford story, save one omission. Unlike so

much of this great town’s heritage, the Mount Pleasant School

Raymond George tried

to ignite a movement to get Mount

Pleasant a historical marker some years back, maybe

have the site turned into a museum or park. The Mount Pleasant School Love Street

Park

The Mount Pleasant School

“Hold

on to the ones you love,

cuz

you never know when you’ll lose them.”

Leonard Smith entered first grade at Mount Pleasant in 1939, three years after it was renamed the Mount Pleasant School. The school’s two classrooms taught nine grades then. Most black students walked to Mount Pleasant from four Weatherford neighborhoods – The Flat (First Monday Trade Day Grounds area), The Hill (West Oak Street area), Sand Town (near Akard & Sloan) and The Neck (near Cherry Park).

Black and white kids played baseball together, had rock fights, and cut up like children still do. Raymond George and some of his white friends walked to school together in the late 1940s. When they reached the Stanley School, the white boys went inside. Raymond kept walking. “That’s just the way it was,” he said.

Mount Pleasant was a two room school, several grades in each classroom. Florine Roddy taught in the southern room, when Raymond was a student. The northern classroom was Lucille Rucker’s. Outside sat two outhouses and a water well whose pipe led over a trough.

“One kid pumped while another drank,” Raymond told me. Raymond remembers there being about fifty students, though that number swelled when migratory families came to town with the railroad or picking cotton. Raymond’s teachers (1946-1953) included Ella Varnell, Lucille Rucker and Mrs. Roddy. “Lucille Rucker built the foundation beneath those black kids’ sense of respect,” Raymond said, “respect for others and for themselves.” Not only was she a good teacher, she was highly regarded by whites and blacks alike. Rucker made the boys play out back and the girls play out front during recess. “She taught us to treat the girls like ladies. Because of her, my generation of students stayed married, kept one job our whole lives, and successfully retired from those same jobs.”

Still, when Mount Pleasant closed, Mrs. Rucker was forced to do odd jobs to survive. “She wasn’t taken care of,” he reflected sadly.

Wilson Hall was added to the northwest edge of the Mount Pleasant campus around 1944. Named after Superintendent Leonard B. Wilson, it was a barracks-like building used for classes and assemblies, with a stage on its west side.

Mount Pleasant sits high atop the western skyline of Weatherford, looking down on the Courthouse to its east. Below its majestic perch, blight stares back from where working black families once raised families.

“Wood-burning stoves sat in the corners of each classroom,” Charlie Simmons told me, “replaced by gas heaters.” Flue holes still puncture the school’s two chimneys. Each large classroom had wood floors and large windows along two walls. One can see daylight looking up through fourteen foot ceilings to the sky.

“These classrooms were filled with little desks,” Charlie told me. “There were kids everywhere.” “Every morning all the kids would walk out here, to the flag pole,” he said. “Say their Pledge of Allegiance and sing a patriotic song.” The flag pole base remains. He showed me where the swings were, the slide, the concrete front porch to Wilson Hall. “We had more fun than you can shake a stick at.”

The schoolhouse road entered from Prince Street, rising up the hill then circling the school. The old schoolhouse sits on private property, contiguous to Love Street Park on its west. This was a time of separate white and black drinking fountains in our city. Blacks couldn’t enter white restaurants (unless they worked there) or attend most theaters. Blacks could buy Texas Theater tickets, as long as they sat in the balcony.

Raymond remembers walking through the Texas Café to the kitchen out back as a little boy, wanting to spin the bar stools around. He couldn’t since the place was whites only.

Weatherford had black churches, a black tabernacle, and a two-story black Masonic Lodge on Fort Worth Highway, east of the courthouse. There were few black businesses. If black students aspired to go to high school, they were on their own.

Raymond and Leonard went to Fort Worth’s I. M. Terrell High School. Most of these kids didn’t have bikes, much less cars to make the thirty-one mile journey each way. Raymond’s dad John Lorenzo “J. L.” George stepped up between 1953 – 1963. He left his upholstery shop twice a day to drive black students to Cowtown in his Ford station wagon at his own expense. Local businessmen later chipped in to buy gas.

When J. L’s car got too crowded, a bus was finally supplied. J. L. spent five hours a day toting school kids, losing this time at his store.

Mitchell Rucker was another pillar of the black community here, born in 1899. “He was respected by the white community,” Raymond told me, “but held at a distance.” In the white community, Rucker was employed at the M & F Bank as a janitor. In the black community, he was superintendent at Prince Memorial for over fifty years, taught classes to Senior Citizens for the WPA in 1944, taught soldiers at Camp Wolters and was a board member at Texas College in Tyler for forty years. Rucker was one of the main conduits between Weatherford’s white and black communities.

“Pappa Ike” Simmons was another black leader. He attended school at Prince Memorial, before Mount Pleasant was built. “Pappa Ike was more of a politician – he knew everybody, running that mouth 100 miles an hour,” Charlie told me. Ike and brother “Uncle Charlie Simmons” each raised families off shining shoes at the Palace or Texas theaters and at barber shops. Many prominent white families had black nannies, butlers, and groundskeepers.

There was a parallel but unseen black society here, one from which trusted black men like Rucker, Pappa Ike and J. L. George could communicate informally with the white establishment. Equally important, several white leaders reached out to the black community – Jack Borden, Borden Seaberry, the Cotton Family, and James and Dorothy Doss, among a few others. Respected whites and blacks interacted, albeit at a distance. Though not treated equally by any means, attacking one group would’ve meant attacking their own.

Mary Kemp remembers when the integration meetings took place in the third floor study hall of the old Weatherford High School. “It was a great time for all, very peaceful. I remember thinking, ‘This is a great historical time.”

Charlie Simmons was one of the first black students at Weatherford High School in 1963. He did well, as hundreds of other black students had before, riding atop the shoulders of Mount Pleasant’s teachers and black leaders. “It was a simple transition,” he said. “Nothing happened.”

This would be another “happily ever after” Weatherford story, save one omission. Unlike so much of this great town’s heritage, the Mount Pleasant School hasn’t been added to the roll call of hallowed historic touchstone sites in our town.

Raymond George tried to ignite a movement to get Mount Pleasant a historical marker some years back, maybe have the site turned into a museum or park. The Mount Pleasant School site and several surrounding acres can be accessed from the city’s Love Street Park and four city streets. The old school’s roof stopped turning back the rain many years ago. This historic place is not long for the world.

The Mount Pleasant School marks a chapter in Weatherford’s history where two communities became one. Unlike much of the South, this town pulled it off peacefully and with respect. As I put my camera back in its case, I noticed graffiti on the wall of Miss Rucker’s last classroom: “Hold on to the ones you love, cuz you never know when you’ll lose them.”

County Poor Farm, A Little Girl in the Woods

County Poor Farm

A Little Girl in the Woods

By Jeff Clark

A Little Girl in the Woods

By Jeff Clark

We may

lose everything.

There's a

depression heading our way. That's what the newspapers tell us. The economic

kind. Here in Weatherford. Nibbling around the edges of our little town -

taking its first taste.

Millions

of everywhere-but-here folks have lost their jobs already. Swept away by the

same tidal wave. Whose shadow we don't yet see. Most in this nation, in this

town, live three paychecks from the abyss. It will frost my britches, if my parents

were right.

A family

doesn't need nice cars, a big house. You don't OWN anything. You can't DO

anything. Why, your father and I made do with so much less. We didn't have to

worry about tomorrow. We didn't have to.

Then a

little girl calls out to me. "I survived," she whispers. "So

must you."

That

young girl's childhood, remembered by her through a prism of almost eighty

years, haunts me this day. She was my storyteller. I didn't see it at the time.

I visited her home expecting a Great Depression story of hardship and woe. That

cup was handed back to me, overflowing. But in the midst of today's woe, her

small farm girl's smiling stories keep bubbling to my surface. In the swirl of

terrible suffering, humiliation, of death, there had been joy. I pull out my

notes from our visit. I listen to her words.

Individuals and families deemed insolvent were "sentenced" to live there, many decades ago. When neither family nor neighbors would take them in. Many were old. Were infirm.

Pride

still governed our society back then. These folks weren't happy to be out

there. They weren't looking for a free ride. Weatherford resident Nila Bielss

Seale remembers those times as a girl. Remembers those people. Her parents, Mr.

and Mrs. Alvin Bielss were the Poor Farm's caretakers. Hired by the county from

the late 1920s through the early 1930s.

"It

was like a big home," she said. "All the people there were like aunts

and uncles. My mother and dad took care of them. They were doctor, nurse, and

psychologist".

The Poor

Farm consisted of two 160 acre tracts of land. The superintendent and his

family had a home out there. The house still stands, barely. There was a

barracks-like dormitory across the road from the family's house. Each Poor Farm

resident had a room off its center hallway. The dormitory had a large porch

across the front where the residents would often gather.

The Poor

Farm's large barn, smaller outbuildings, and a water trough inscribed by Nila's

daddy in 1923 also still remain. There's also a shack of a house off by itself,

being eaten alive by a tree, shared back then by a blind man and the farm's

Delco electrical system.

Joe C.

Moore was one of the early Parker County Commissioners. He reflected on the

court's thinking in starting the poor farm, in a Weatherford Weekly Herald

story September 21, 1911: "Editor: I desire to answer some of your

questions as to why the county poor farm was purchased, how used and what

revenue it produced. About 1881, soon after A. J. Hunter was elected county

judge, B.C. Tarkinton, Joe C. Moore, Frank Barnett and W. A. Massey were

commissioners. After an investigation, this court found that other counties had

farms that were a source of good revenue, a large savings to the taxpayers, and

a good thing in general."

"George

Abbott and wife were employed to superintend the farm with instructions to feed

and clothe well all inmates of the farm, and to give each of the inmates a task

according to their fittedness or ability."

The farm

was free and clear of debt after only three years. The commissioners additionally

used jail inmates to work at the farm. They received credit against their

sentences.

All

thirty-eight paupers under the county's financial support were then notified of

the day and time to assemble, to be taken to the Poor Farm. Steaming Nazi

locomotives pulling wooden-slatted cattle cars pop into my imagination as I

write this. Though that's probably not fair. I'm sure some thought, in Parker County

Apparently

only about half showed up, Mr. Moore tells us, "showing that the county

had been paying out money to those who had other means of support." No

such testing goes on today. Far as I know.

The Poor

Farm usually had between fourteen and twenty people living there at any one

time. Those that were able worked in the fields, gathered eggs, raised hogs and

cattle, milked or helped cook and clean back at the dormitory.

Aunt

Mary, one of the residents there, was a cook while the Bielss Family lived

there. The woman showed kindness to young Nila. "Aunt Mary made the best

tea cakes," she remembered. Once Nila's pet goat Billy, who followed Nila

everywhere, somehow got into Aunt Mary's room when the little girl was

visiting. Though Billy created quite a mess, Aunt Mary, known for her

organization and cleanliness, acted like nothing had happened.

Aunt Mary

grew tired in her later years and decided she was not going to help out around

the farm any longer. Her back was bothering her, she said. She could no longer

get around, she told some others. One afternoon, Nila's dad came up to the

dormitory's porch, where Aunt Mary was still feigning illness. He let a

harmless snake loose that promptly sought Aunt Mary out. Terrified of snakes,

she leapt from her chair and took off, promptly cured of her affliction.

"We

were almost totally self-sufficient," Nila said. "The people there

were very busy people. My mother and dad alternated each month in buying

groceries. Mother would get mad if the grocery bill was over twenty dollars for

the month (for about eighteen people). My dad butchered hogs after the first

cold spell and cured the meat. The cellar was full - the walls were lined with

fruits and vegetables my mother put up."

During

harvest season, when they would thresh the wheat, county commissioners would

pay people from Weatherford one dollar a day to work (during the Great

Depression). And people from town would come out, to help out - to get paid.

Nila's dad would salt meat and hang it from the rafters. When Poor Farm folks became ill, her mother or dad would sit up all night with them.

Nila's dad would salt meat and hang it from the rafters. When Poor Farm folks became ill, her mother or dad would sit up all night with them.

Nila had

a horse as a little girl. The commissioners apparently had confiscated the

animal from someone, to stop its abuse. "The horse wasn't quite

right," she remembered. "He would be perfectly sweet and

normal, then all of the sudden just go crazy for a little bit." Nila loved

that horse. One day she was riding him up by the big barn, through some old

tree stumps. The horse had one of his episodes. Threw her through the air and

onto the ground. Her dad was nearby. Thank goodness. Made sure she was okay.

She remembers this part. He told her to get right back up on that horse. So she

did.

The Poor

Farm owned a few other horses to pull the plows and wagons, even a couple of

Percherons at one point. Nila remembers her dad being partial to mules. These

teams would take corn to the gin in Granbury in a wagon, and would help harvest

the wheat. When it was ready.

Nila's

father often woke up at 3 a.m.

to begin his endless work around the farm. Near the end, most of the farm's

residents were advanced in age. Were not a lot of help.

"Daddy liked to whistle," Nila told me. "He was known for that. You could hear him, even at three in the morning, out there whistling." He was a deacon in the local church, where her mom taught Sunday School and played the piano. Before they were married, Mr. Bielss had to sell his beloved horse Penny. He needed the money. He wanted a proper wedding ring. He sacrificed.

"Daddy liked to whistle," Nila told me. "He was known for that. You could hear him, even at three in the morning, out there whistling." He was a deacon in the local church, where her mom taught Sunday School and played the piano. Before they were married, Mr. Bielss had to sell his beloved horse Penny. He needed the money. He wanted a proper wedding ring. He sacrificed.

Nila's

folks were good people, were hard workers. Nobody helped them out much except

for Moses, Mr. Taylor, and sometimes Aunt Mary. "Mr. Taylor, who was

blind, would want to help out more, but we were always afraid for him, when he

got around the big saw," Nila told me. He was a nice man, she said. Mr. Taylor.

Nila remembers

her family having a small record player. One day she and her brother Eldon were

playing "He'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain" so loud that her mother

could hear it down the hill. They got into a storm of trouble. Before

electricity was common, the farm had a Delco unit powered by a windmill to run

a few things, like the single bulbs that hung from a few of the ceilings. The

Delco was located in same little house that Mr. Taylor lived in. The blind

gentleman.

Poor Farm

residents washed their clothes in big black number five wash pots. The man

named Moses kept pecans in a Maxwell Coffee can. He cut those pecans into

laser-perfect halves. Moses did. Moses was paralyzed on one side. Had a peg leg

that he made himself.

Nila told

me about Mrs. Baker, who'd been addled after being struck by lightning. It

stayed with her. Mrs. Baker. Whenever a storm approached, Nila's parents had to

comfort her fears.

Nila told

tales of a happy childhood at the farm. At the Poor Farm. Where her parents

took care of so many. Nila never lacked for anything, she wanted me to know.

Nila bottle fed her goats. Had a menagerie of livestock to keep her

entertained. She listened to Little Orphan Annie on the family's radio.

Around

1946 the dormitory building where the residents lived was moved to the 100

block of Throckmorton in Weatherford. It there served as a home for the aged.

The move was the end of the true operation of the Poor Farm. The building was

later relocated to Rusk Street ,

where it still stands.

I drive past it. Often. Though I've never ventured up to it. Wouldn't be polite.

After World War II, the federal and state governments increased social services for the poor and the elderly. For the nation. Not justParker County

I drive past it. Often. Though I've never ventured up to it. Wouldn't be polite.

After World War II, the federal and state governments increased social services for the poor and the elderly. For the nation. Not just

The Poor

Farm pauper cemetery still sleeps off in the woods. The place was forgotten

until the early 1980s, rediscovered by a group of hunters. It appeared to have

about forty adult graves. And one child's grave. No one knows for sure.

The

earliest documented burial was 1904. The lonely site had no fence. At that time

the county commissioners were considering selling the farm. The Parker County

Historical Commission persuaded commissioners to let them restore the dignity

of the cemetery. This, they did.

Later in

1986 a historic marker was awarded by the state, now visible from Tin Top Road . A

right-of-way was established from Tin Top to the cemetery. The Parker County

Abandoned Cemetery Association continues to maintain the cemetery, with the

help of donations. They do this, to this day.

I need to

finish this story. There's much to do. To prepare for. I feel nauseous. Unsure.

I need a

snake to scare me off this porch.

One man

living at the Poor Farm was insistent that he not end up in the pauper

cemetery. When the time came, Mr. Bielss buried him off in the woods. Wayne

Thompson, who ran a dairy on the property in the 1950s remembers three lone

graves off together near a lone tree, about a half mile away. This man's

presumed to be one of the three. But I'm not sure.

J. G.

Godley's death was particularly tragic. Godley died of suicide November 11, 1929 . Nila

recalls that Godley was once a wealthy man (related to the family that started

the Godley community to our south). He was divorced, was 87 at the time of his

passing. He apparently squandered his fortune and died a pauper at the farm. He

was always very bitter and depressed, Nila told me. Many times he pleaded with

her dad to kill him.

One morning the Bielss Family was having breakfast. Before sunrise. The cows down the hill started bawling. Her dad got his lantern. Said he'd better go check on what was wrong. On what was the matter.

One morning the Bielss Family was having breakfast. Before sunrise. The cows down the hill started bawling. Her dad got his lantern. Said he'd better go check on what was wrong. On what was the matter.

Mr.

Godley had cut his throat inside the farm's two hole privy. In the Poor Farm's

out house. He lay dead on the floor. The county death certificate lists no relatives

and no birthdate. The November 12, 19 29Austin . I never found her.

Nila

remembers Mr. Godley being buried outside the paupers' cemetery fence by her

father. County records show his final resting place as Oakland Cemetery

The Poor

Farm Cemetery has one of the highest ratios of unmarked graves in Parker County

Association

members Mary Kemp and Billie Bell spent long hours going through records trying

to learn the names of those interred at this cemetery. Mary helped me with this

story. Nila was its ringside witness.

I don't

know how this story comes out. The Poor Farm. Parker County

We could

be in for the surprise of our lives.

The Poor

Farm woods south of Weatherford probably hold this nation's answer. The souls

in that graveyard. The whispers in those trees.Those times seem so foreign.

Listening to that little girl. To the slip-sliding past. Our future's out

there. A cradled secret, walking around in the faded front overalls pocket of

another time. But those folks aren't talking. Not today. Not to me.

SUGGESTED CAPTIONS

Depression-Era

residents sit on the front porch of the Poor Farm Dorm.

Nila’s

Family near the Poor Farm barnyard.

Thursday, December 5, 2013

Sometimes you just have to pay attention...look what's around. Why would THIS be sitting HERE. If man made it, there's a reason (at least in most zip codes). The T & P Railroad, as it chuggged east to west through our stretch of Texas, had to stop for water at pre-determined intervals (1 - 3 miles sometimes). We're used to seeing the wooden elevated water tanks near train depots from childhood Western movies, but sometimes, if a stream ran nearby, the crew that built the railroad also dammed up the stream for the locomotives to drink.

Monday, December 2, 2013

Eternal warrior

I’m told a story several days back, here in Eastland County,

by a man, on some land, not too far away from where I now stand. ‘That his

great grandfather was walking through these woods we’re standing in now, way

back, noticing the tip of a feather protruding from the ground. Sticking up

through the leaves, like a stalk of grass, between two ridges of rock.

The tip of a feather.

His great grandfather dug down, this now man said,

discovering an Indian war bonnet, then below, this man looked me in the eye, the

remains of an Indian beneath the bonnet, wearing it, seated astride a warhorse,

the horse still standing, also, very much dead, from many years of waiting

there, between two vertical shelves of rock. ‘Ready to lead his warriors into

battle inside the far banks of eternity.

Surely that would be heaven, for a warrior.

The setting, a forest of tall oaks on a steep hillside of

house-size boulders, flaking off the east side of the rise above a stream, like Edsels sliding off the edge of an overpass. The stream would’ve been live

water, back then.

Are we standing in a Native graveyard, a portal to something

better? The karma felt right, though words are only words, are only words, are only words, after

all, I’ve recently learned.

He said to me, as we moved up the path to another tale, “The

grave was desecrated back then. They didn’t know any better. The war bonnet is

an heirloom in my family, even now…”

Friday, November 29, 2013

Where Did You Go?

You let me down.

My gas gauge

blinking E for the last twelve miles.

I pulled into your

gas station. Desperate.

Your sign says

“Gas, Oil & Parts”. Such a kidder.

I’ve been inching

down your too-slender Bankhead

Highway , now Finley Road, west of Putnam. Callahan County

In a Model T, I’d

have wide pavement to spare. Today, much faster than twenty and I’d be sucking bar

ditch dirt.

Nothing to see

here.

I passed a granite

Texas Centennial Marker back up the road, surrounded by turkey vultures atop

hack-cedar fence posts. The 1874-1875 military telegraph line crossed there,

connecting Fort Concho Fort Griffin

The year Comanche

Natives were herded north.

No coincidence,

that.

Black and white

stripes mark the center spine of your phantom road west. No shoulders. No

signs. No billboards.

No gas.

I’ve crossed four

dying bridges coasting to this place, rusted rebar finger bones poking through

crumbling concrete guard rails. The Model As of long ago safe from raging flood

waters that came along once a year, or not.

Is that your frame

house behind the gas station, back in the trees, fallen to the ground? Abandoned

or fled or did you just move on? Disgraced in every way but fire.

Are you back there,

hiding from me in those shadows?

Your neighbor’s

farm house crowds us, from across the road. I bet they made you uncomfortable,

right there when your customers pulled up. A dad or widowed grandmother once

answering that front door. Unlike yours, their empty home stands proud. Shoulda

seen to that leak in the roof…

I hear the monster

that killed you, if you’re dead, roaring low over my left shoulder.

Interstate 20,

though it looks like you skedaddled before that Faster-Better-Longer blew

through and spoiled your fun.

Will great

grandkids explore that abandoned four-lane someday, they distracted from Whatever

Comes Next?

Will they mourn

the eccentricities of their ancestors,

Even know their

names?

Our names?

I know you’re

here. Need you to be here.

But again today,

Like yesterday,

Like tomorrow, you’re

not.

Best wishes,

wherever you are.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)