Zim Zimicki’s Hard Work

Fuels America’s Trip West

Driving

a Model A Ford from Weatherford to Ranger in 1928, I would’ve been worn out by

the time I hit Strawn. My average speed was 35 miles an hour. Pulling off the Bankhead Alternate Highway

at the first gas station I found, Marche

“Zim” Zimicki might have greeted me, might have shown me around. I made such a

trek Thursday, not in a Model A (and more than a little bit faster). Viewing

all that Zim left behind felt like a warm handshake between new friends. Zim

passed away in 1962.

Traveling

from my home to Ranger back when Zim built this place, drivers followed the Bankhead

Highway from Weatherford to Mineral Wells, to Palo Pinto, toward Metcalf Gap, then

they turned south to Strawn, finally attempting one steep hill west up into

Ranger. The Thurber brick-paved Bankhead

Highway was cobbled together from a patchwork

quilt of older already-existing county roads, America’s first transcontinental

highway.

Cross-country auto

travel offered high adventure after WWI, not for the faint of heart. Cars often

carried two spare tires in case of flats. The “Monkey Grip” cold-patch kit,

with glue and about 100 little rubber patches to fix inner tube holes was as

necessary as extra tanks of water for overheated radiators. My uncle could’ve

followed me in a second car, if our family now was as large as it was back then.

When one car “quit” (broke down), the other could tow its fallen brother to the

next mechanic.

Giant billboards of

the time lured westbound drivers approaching Metcalf Gap south to Strawn, onto the

Bankhead Highway Alternate (now Hwy. 16) or west across the historic gap to

Breckenridge. Think Route 66. At slow speeds with a car full of kin, boredom (or

madness) quickly set in. Approaching Strawn from the north, stopping at Zim’s Quality

Beverages to get “fuel-eats-drinks & ice”, use the outhouse and even stay

in the motor court would’ve been mighty tempting.

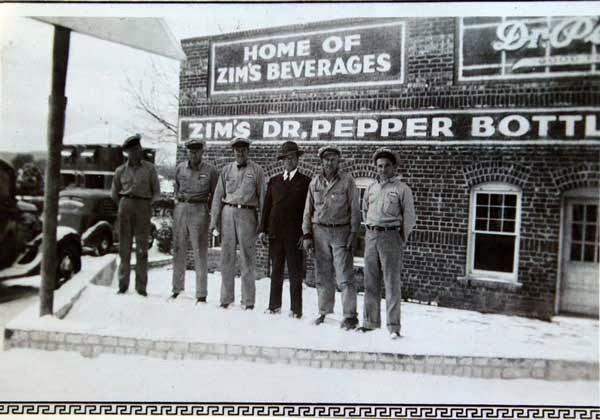

Zim’s brick

service station – restaurant – Dr. Pepper bottling plant stretched along the

west side of the two-lane highway, just south of the first Palo Pinto Creek

bridge (past the Necessity cutoff). The mid-October morning I visited, 42 degree

silence greeted my arrival. I crawled out and walked across brick pavers to survey

the abandoned brick gas station, the rotting wooden overhangs held aloft by iron

tie-rods. Twenty Model A’s or Model T’s could’ve packed this station, back in

the day.

My Model A now full

of gas, I might have eased down the hill to the Y intersection at the filling

station’s left. Travelers veered left to the Dr. Pepper bottling plant or right

to the tourist court. I opened the gate to the right (with permission). Walking

beneath towering pecan trees, one quickly realizes there’s more here than meets

the eye. The one story “filling station” visible from Highway 16 conceals a two

story labyrinth, housing a gas station (four pumps), restaurant, bar, cavernous

machine shop, bank, office, kitchen and more.

Back then, a

muffled clattering vibration sound would have come from the south. Across the

courtyard a hulking brick warehouse that once housed the Dr. Pepper (and Coca

Cola) bottling plant stares back, once supplying soft drinks to this part of

the state. A “Zim’s Quality Beverages” billboard painted on its side invited

passersby to pull off the highway. West from there, a five bay Dr. Pepper delivery

truck garage connects. Shooting north, five fallen-in tourist court motel room

shells sit abandoned, the forerunner to the modern motel.

“Kids need to be

kept busy,” Zim might have told me, showing me around. There was a small gold fish

pond in the days before color TV. Families could also venture south to Zim’s

swimming hole in Palo Pinto Creek, just below the Watson House (now Edwards

Funeral Home). It was shady and had a rope swing. There’s a story about a

handicapped boy on crutches looking down at this swimming hole from the Watson

House. The embankment caved in, the boy fell in the creek and drowned.

The first thing

you notice about Zim’s buildings is the handsome brick work completed by Zim’s

father-in-law, Pete (“Piotr) Wasieleski. When Thurber’s mines began to wind

down around 1921, Pete began working for Zim. Atop gentle wall arches facing

the highway, three small round brick parapets crown each capital (think a rook

in chess), their symbolism lost to time. The tumbled burgundy bricks lend the

building a warm glow in morning sunlight. Ornate arched brick drains and

soldiered brick accents above windows reveal artistry uncommon today.

“This land looks awfully low,” I might have

suggested to Zim. He would have smiled. Pointing back toward the main highway building,

you come to understand that Zim created this place to “fit”. The Bankhead’s

roadbed soars fifteen feet above the bottomland you’re standing on. Zim snuggled

his two story station against that roadbed. Its second floor fronts the road

(was high enough). The bottom floor faces the other direction, sitting

comfortably on the ground. Elaborate stone-lined ditches channel rain water to

the creek. One rock-lined channel travels under the entire length of the main

complex. Fit your building to the land, not the land to your building. Think

Frank Lloyd Wright.

Marche (MARCH-EE) “Zim” Zimicki was born in

1897 in Pennsylvania’s

rough-and-tumble coal fields. His family (originally Zamitzski) worked in Thurber’s

mines by 1900, moving to Lyra’s mines by 1910 (between Strawn and Mingus). Being

the only boy (three sisters), Zim and dad Pete worked in the mine and farmed

(graffiti on a nearby water well records “Marche 1917”). Zim may have started mining

as young as 13.

When Zim returned

from WWI, capitalism’s wheel began to spin more rapidly in this creek bottom.

Zim took a job nobody wanted, tearing down the old Stephens County Courthouse

in Breckenridge in 30 days. One wonders if some of the pressed tin ceilings above

the gas pumps come from that facility. Streamlining his family name for “only

in America

success”, Zamitzski became Zimicki.

Father and son

pooled their income, giving them the stroke needed to buy these twenty acres

along the northern branch of Palo Pinto Creek. Other nearby land holdings were

added at bargain-basement prices during the Great Depression.

Zim must’ve

absorbed the Thurber “vertical integration” that Colonel Hunter and W. K.

Gordon infused into Texas and Pacific Coal operations, offering coal miners not

only a place to work, but providing for their human needs with company stores,

bars, church buildings, even a cemetery. Zim dreamed of satisfying a similar menu

of his visiting Bankhead Highway

guests’ needs on their journey toward the Pacific.

This

complex was and is a work in progress. Begun in the 1920s, major construction

took about a year to complete. Zim built the gas station, then the restaurant,

ice house, bottling plant, and travel courts. Though run by family and staff, Zim

could be seen everywhere, doing everything. Zim dressed plainly, not being a

“behind the scenes pencil pusher.” Before we arrived, he likely just crawled

out from under a truck, rebuilding its transmission.

Zim also mastered

the load-bearing engineering he observed in the overhead wooden timbers holding

up the uncertain ceilings inside Thurber’s deep coal mines. Zim’s ground floor

machine shop’s ceiling reveals strong concrete beams atop solid columns

carrying the weight of the entire suspended second floor.

Zim built his own

power plant to supply electricity to the complex using a large diesel motor. To

start the diesel engine, one had to light a wick (in place of a spark plug) and

stick it in a hole (filled with gas) while cranking the engine. This required a

man of deep faith (or great speed).

Zim owned the Dr.

Pepper and Coca Cola franchises simultaneously for awhile. Coke asked Zim to tie

into Strawn’s city water and stop using his well water (still in operation).

Zim told them to go to hell (diplomacy not among his virtues). Today’s Strawn

Museum (open 11 – 4, Thursday - Saturday) houses several versions of Zim’s

Quality Beverages heavy, opaque Dr. Pepper and Coca Cola bottles, listing

Breckenridge, Strawn and Cisco as his territory. Zim might’ve also leaned toward

Dr. Pepper, as they also offered Crème Soda, Lemon, Lime and Strawberry drinks

in their lineup.

Zim’s ground floor

machine shop was always turning out clever gadgets – inventions, cattle guards,

truck repairs, and gates. Old truck frames converted into work benches still do

their duty. Discarded tin Coca-Cola signs hang from the black-dark ceiling awaiting

their next assignment. Zim received a patent for delivery truck racks that

allowed drink cases to slide forward on rollers when other cases were removed.

He built a revolving cross for Strawn’s St.

John’s Catholic Church bell tower, though this was

never installed.

Zim

had a bar on the second floor. Accessed from the highway’s front door or up a

winding stairway from the bocci ball courts below, one delights in the stout wooden

columns that frame large mirrors behind the bar. There’s a kitchen to one side,

a wood-planked dining room/dance hall to the north. “It happened right here,” I

felt the room’s shadows whispering, though what happened there, I may never

know.

The new owner, a

kind man, lifted one of the barstool seats from its pedestal and turned it

over. The seats were made from truck hubs, fitted onto cams atop their poles

below, just like a delivery truck’s axle. I know Zim is smiling in heaven as I

reveal his ingenuity and thrift. The bar counter’s base features corners of

ridged glass blocks. The juke box surely played country swing dance tunes as working

class couples circled the dance floor, gold-trimmed ceiling fans click-clocking

lazy circles into the pre-air conditioning summertime air.

Between the

restaurant and the backyard tourist court sat picnic tables, barbeque pits and bocci

ball courts under shade trees providing travelers a much needed overnight

oasis. The southern room of the filling station still boasts a full-sized bank

safe built into the wall. There’s a story that Zim had a little bank for

awhile, though sheltering Zim’s steady cash flow seems as likely (or perhaps a

lack of trust in post-Depression banks).

Under the highway

bridge outside one observes graffiti, colorfully modern and vintage. One scribe

writes “Wiley Wells…From Buffalo, N.Y…going to God’s country. March 29, 1929.” I hope Wiley made

it. Seven months later, Mr. Wells’ young nation plunged headlong beneath the

waves of its first Great Depression.

“Zim was tight-fisted, inventive, and versatile,”

remembers nephew Leo Bielinski, “and quite an accordion player.” In the late

1940s, Edward Dumith was building a home in Mingus. Being Zim’s friend, Dumith

hoped to buy some of the old (but solid) lumber salvaged from the Stephens

County Courthouse at a “buddy” price. No such luck. Dumith could’ve bought

lumber from the lumber yard at the same price. Zim used old Magnolia Beer signs

to flash the bottling plant’s roof. He used discarded Coca-Cola signs to form

the restaurant’s stout structural concrete foundations.

One

neighbor child remembers an army of people constructing Zim’s. As Thurber, Mineral City and other area coal mines were winding

down, cheap labor was plentiful. These ex-coal miners (doing the work of three

men today) did the heavy lifting, with Zim leading the way. In addition to

Wasieleski, Zim’s brother-in-law Big Joe Daskevich helped construct the

buildings, later rising to become bottling supervisor. Zim’s dad Pete (then

about 55) was also an old miner who could handle hard work.

Family helped Zim

achieve his dreams. Zim’s second generation immigrant imagination helped

provide for his family and employees during wrenching economic times. At family

gatherings Zim played his accordion. Wife Stella kept the books. When Zim and

Stella married, they built a small two-bedroom wood home just south of the

bottling works. With all of their wealth, they continued to live there until

1960, when they built the still-standing two story brick home just west of the

original house.

Zim

wasn’t famous for paying high wages. When he bought ranchland around Strawn in

1938, Frank Bielinski and Tut Daskevich were paid $1.50 a day digging post

holes by hand, ten hours a day. Of course, like today, any job was a blessing. When

Zim’s son (Marche Pete) asked his dad to help pay for his senior year at Texas

A & M vet school, Big Zim said, “Gosh, Marche, this school is costing too much. It

might be cheaper if I just bought the damn school myself.”

When

the highway connecting Weatherford to Ranger was finally completed in the 1930s,

it effectively killed Zim’s roadside business. He went into ranching, never

missing a beat.

I was tipped to

look for a hidden compartment built beneath the highway or bridge, to conceal

beer or moonshine. I found no evidence of that. Zim didn’t produce moonshine,

both because of his upright wife Stella and because it would’ve exposed his

prosperous business to seizure by federal revenuers. Hiding his own hootch from

his eagle-eyed wife Stella, however, keeping her from knowing he was “nipping

at the bottle” was certainly a possibility.

Zim did own a

honky tonk to the north in Metcalf Gap after Prohibition was repealed. This was

a rough place, frequented by thirsty cedar hackers (talk about hard work). But

Zim was all about making money. When beer cans came along, most drinkers used a

“key” to open them. Zim invented a foot-operated can opener for his bartenders,

to speed his liquid commerce along.

Shortly before

Zim’s death, he was asked to speak to the Strawn Lion’s Club. He told this

story: “It was a full moonlit night, freezing cold. The birds had nothing to

eat and they were miserable. But an old bull in the corral had just let a nice

steaming cow pie. A mockingbird flew down and gobbled this up. Now he was warm,

and full, and contented, so he began to loudly sing. The disturbed rancher who

was trying to fall asleep grabbed his 12-gauge and blew the bird away. The moral

of this story: When you’re full of BS, keep your mouth shut.”

Zim

finally sold the Dr. Pepper bottling operation to M. L. King in 1937, who moved

it to Ranger. One also finds Zim’s Heileman Brewing distributorship flyers (with

offices in Strawn, San Angelo

and Big Spring)

among historic Zim literature. The multiple offerings of all Zim’s enterprises

may never be known.

Zim

would have been pleased, I think, that another visitor to his American dream got

what he came for. Several that lived in the Strawn area and many that traveled

through it came to know the man Zim Zimicki by his works. I add myself to that

list. The day warmed as I climbed in my car and drove away.