Dr. Jackson Evans brings 1872

medicine to Eastland County

We

left the pavement seven miles ago. The time machine dial rolls backwards –

2008, 1941, 1917, stopping at 1872. We’re bouncing, twisting and turning

through Eastland County ’s

vast Palo Pinto Mountains Evans

Cemetery

Jackson Evans was

the first physician to permanently settle in Eastland County Eastland

County

I try to imagine

what this rough country looked like back then. Take away the mesquites, most of

the cedar. The Evans came to this ridge March 10, 1872, after a short stay at

the Allen Fort, a mile down the hill from here. Why did they pick this hidden

mountaintop? Comanches would terrorize these hills for three more years.

We reach the final

clearing, surrounded by cedar and majestic oak. The original arch-topped iron

fence surrounds the Evans Family’s final resting place, maybe forty feet square.

Bessie Hill, the

Evans older daughter, died first in 1894. Her grave is the center anchor to

this cemetery, covered with knee high crepe myrtles. This plot was overgrown

for many years, but the invading trees and brush (and rattlesnakes) have been

cleared. Good people.

Dr. Evans reports

that 1870s Eastland

County Eastland

County

Jackson Evans was

sent to school at the University in Oxford ,

Mississippi New Orleans . Dr. Evans tended the sick and

wounded during the War of Northern Aggression (Civil War).

Mrs. George Langston’s

“History of Eastland County, Texas” reports that one of Dr. Evans’ first calls in

Eastland County Erath

County

He covered a huge

swath of wilderness on horseback, then by buckboard driven by his daughter Alice.

His saddlebags were fitted to hold glass vials of medicine. Dirt poor settlers

might pay Dr. Evans in chickens or pigs, or not at all. A small fortune in

uncollected fees remained on the books when he died thirty years later.

The time machine

has been kind to these woods. The trees were thinner back then, more brush,

taller grass, more “shinery”. Some sounds stuck with this land – wild hogs, fawns

running through the thickets, rattlesnakes. Today, thankfully, no Comanche war

cries.

Dr. Evans wife

Maria presents an even bigger mystery.

She married Jackson in 1863 at her

father’s plantation in Sumpter Hill , Alabama Jackson

met Maria while she was teaching at a girl’s seminary established by her father

in Meridian , Mississippi Pendleton , South Carolina Plantation life did not follow Maria to this savage corner

of Texas .

The second Evans daughter, Alice, wrote

that “mother was often left alone with us three small children, often at night

and through the long days, but she was always so cheerful and brave, we never

knew that danger might be lurking near…Her life here, reminds one of the

missionary in a far country, as she cared for all who came and sought the

Doctor's care and in her Christian faith and integrity, had an uplifting

influence on all with whom she came in contact.”

The old wagon road to their house left the

main road between Blair’s Fort (later Desdemona) and North Fork (later Strawn),

tracing the slope of a creek as it climbed over a hundred feet in elevation to

their corral.

We retrace our

steps. Across a small meadow, a stacked rock chimney peeks out of the dense

brush, the crown of the original Evans log cabin, over twenty-five feet in the

air. Cabin logs lie rotting in the brush.

Dr. Evans grasped

the sacrifices his family made. “My three children were then very small, but I

had often to leave them and their mother alone when there was danger of

Indians. We stopped near a cow-ranch for protection – as there was no town in

the county – and we are still at our old stand with all the practice I can do.”

Dr. Evans’ land holdings exceeded 2,000 acres at one point. The family raised

cattle and horses. “They planted one of the first orchards in the

county, and Maria dried peaches, apricots, and apples for use during the winter,”

a granddaughter tells us. “Deer, turkey, bear and an occasional piece of

buffalo meat brought by a passing hunter were diet staples. Such luxury items

as coffee, sugar and wheat flour were scarce because supplies had to be hauled

from Waco or Fort Worth . My grandmother recalls that her

father received a box of medicines from Stephenville which arrived before

Christmas with some red stick candy and a note saying ‘for the children, from

Dr. West’.”

Mrs. Evans raised

the children, nursed her husband’s patients, ran the kitchen, and educated her children.

She later taught at the first school located at the Allen Fort.

It’s

time to leave. There’s a light wind in the trees. The smell of cedar. There are

no sirens, car horns, pump jacks or airplanes. We are standing in true wilderness,

at the front door of a family that helped birth Eastland County

This story is excerpted from the book

“Tabernacle – The Back Road to Alameda

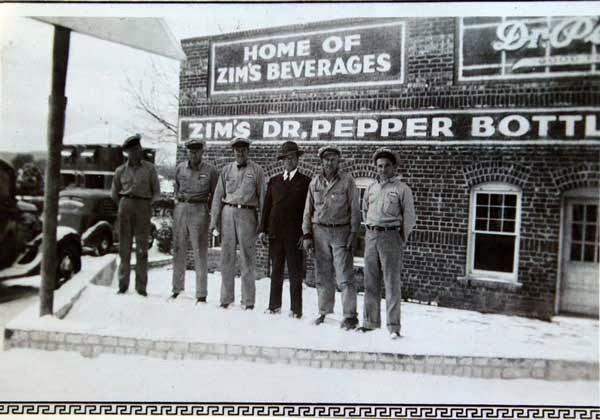

SUGGESTED CAPTIONS

1.

Dr. Jackson Evans, first doctor in Eastland County

2.

Evans Homestead chimney peaking through the brush.

3.

The Evans

Cemetery

4.

Dr. and Mrs. Evans headstone, both born in 1837, both

passing in 1908.

No comments:

Post a Comment