The Texas Tabernacle contains writings and photos about the people and history of the Palo Pinto River and the Leon River Country, Eastland, Palo Pinto and Stephens County, maybe old friends and detours that will likely occur along the way. I like to look for the old things...events that happened, or maybe should have. Listen to what they have to say.

Everything Matters

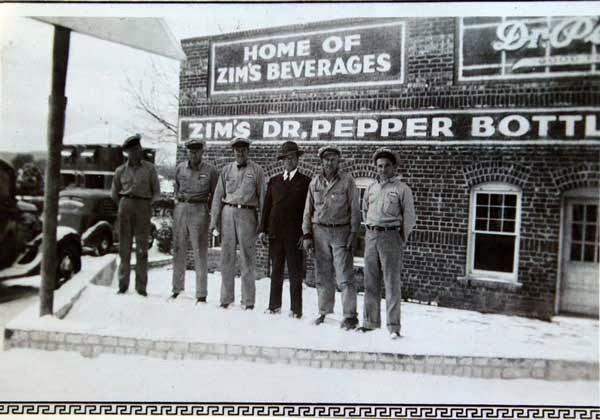

Zim's Bottling of Strawn

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Homestead - Eastland-Erath County Line

Visited yesterday, beside a stream we had to cross, between the protection of tall mountains, a flat fertile field, once cleared, now covered with upstart mesquite and cedar, a debris field of brown rough rock stones that could've held the log cabin, a well, stacked rock walls behind, from clearing that field, keeping in the livestock. The old road, the one on the treasure map, finally found through cleared trees to the east, crossing the stream once, maybe twice. Did he, they, the family move on...their old home, this dry stack of rocks standing vertical over 100 years, sleeping in rough country that has to date been silent to the next generations?

Farther east, seeking a second homesite, a neighbor once, according to the map, X marks the spot, another road, easily visible here and there, up wrapping the tall hill, still visible mostly, a strange place for a cabin really, not much in the way of flat but a million-dollar view, maybe a pioneer who needed lead time should visitors show up, connecting to this road, the one that led to this first homestead. We didn't find much or really anything left behind from this second cabin...some old felled tree stumps, a couple of "don't belong" holes, like ones to the east at the neighbor's, cisterns or cellars or where tree root balls fell, laughing later at our rich imaginations.

A good morning. November 28, 2014. The first homestead, undated, late 1800s based on another neighbor, an almost twin I've seen above six miles away. On a survey named after a man whose homestead this is not. His farther west, up on the rise, also still there, mocking the pavement who slithers nearby, in a hurry, with a purpose, unaware.

Same story, another frontier chapter...I hope they made it where they were going. Or were happy here, somehow, an equal then growing mystery.

Saturday, November 22, 2014

B-17F Crashes and Burns Four Miles South of Mineral Wells

B-17F Crashes and Burns

Four Miles South of Mineral Wells

By Jeff Clark

“Thank you

for your request. Attached is a copy of the accident report covering the loss

of B-17F, s/n 42-5719, at Mineral Wells TX on 11 March 1943…We hope this

information is of value to you.”

I’m staring

at a faded copy of a “War Department – U.S. Army Air Forces Report of Aircraft

Accident.” The men flying that plane are no longer around to interview. This

sheaf of papers will have to tell their story.

First Lieutenant

Jack A. Nilsson; 2nd Lieutenant William F. Pitts of March Field , California Texas ;

Sergeant Jamieson P. Ware of Dallas ;

William R. Thaman of Ohio ;

Corporal Olen G. Diggs of Lubbock

and Private Joseph F. Yonack of Dallas

are recorded on the Personnel Listing.

Nilsson was

Pilot Instructor for the training mission, with Pitts and Regan on board as

student pilots. Five enlisted men rounded out their crew. All were stationed at

the Army Air Forces Advanced Flying

School Hobbs Field ,

New Mexico

There is an

extensive listing of damage, of what investigators found smoldering on the

ground. By the time you read this, this plane crash’s anniversary will be two

weeks away.

The men’s

B-17F is known as a “flying fortress” four-engine heavy bomber, developed in

the 1930s, a high-flying aircraft able to suffer massive combat damage and still

stay in the air. The B-17 dropped more bombs than any other aircraft type

during WWII.

This fated

plane took off from Hobbs Army Air base on a navigational training flight March 11, 19 43

Nilsson

writes, “I knew the weather was bad at Fort Worth…We had approximately 2,500

gallons of gasoline aboard and only a 6 ½ hour flight to make.” They pushed

along at 180 mph for the first two hours, hoping to beat worsening weather developing

around Cowtown.

Nilsson

recalculated fuel consumption. “I discovered we were consuming it at an extravagant

rate”. They throttled back to 1,850 RPMs. Speed dropped to 160 mph.

As they

approached Amarillo

around 1615 hours, transmitter trouble prevented them from making radio contact

until they were 40 miles east. They were told to proceed to Tulsa . About 60 miles southeast of Tulsa , electrical storms

prevented them from keeping radio contact with Shreveport . Nilsson relates “the static was

so severe that we couldn’t hear the S.

P. Range

The report states that except for

“excessive fuel consumption and increasingly bad weather,” the flight was

normal until the plane left Shreveport .

It began to pick up ice. The pitot tube froze (used to measure air speed), but pilot

heat was turned on and the instrument came back online. The pilot lifted the

plane to escape icing and to maintain radio contact. Student Pilot Pitts said,

“My radio would go out when I got into the clouds. We got over Shreveport so we could follow the beam and

this side of Shreveport

we ran into an electrical storm…When I got into the overcast, the radio

wouldn’t work at all.” Rounding Shreveport ,

the plane turned east toward Dallas .

Cruising at

14,000 feet on the way to Dallas ,

they ran into large build ups of clouds and again started to pick up ice. They

had to climb to 18,000 feet to get above the icing and retain radio contact.

As they

approached Dallas ,

they dropped down into the overcast at 14,000 feet. They maintained radio

contact this time. When they were over Dallas Radio Station at 2030 CWT , the ceiling in Fort Worth was reported at 800 feet.

Pilot Pitts

remembered, “As we came into Fort Worth and went on out the north leg for

procedure let down, the ceiling dropped to 300 feet and in a very little while

it was down to 100 feet and he told us to go to Abilene. As I was going around

to make a 180 degree turn to come back onto the beam, my No. 1 engine went out….we

were at 3,000 feet then.” The three-bladed prop fell silent.

Nilsson reached down between his

student pilot and copilot and pushed the feathering button to reduce drag. The

oil pressure slowly dropped to 30 lbs. They were advised there was an airliner

coming in underneath them somewhere.

The crippled plane managed to climb

to 8,000 feet on their three remaining engines. They only had 600 gallons

remaining, enough for two more hours of flight. Nilsson transferred the gas

from their silent No. 1 engine to the remaining three engines. He believed he

could make it all the way back to Hobbs

if he had to.

“The co-pilot and I trimmed ship as

fast as possible, with full right rudder,” Pitts said. “Both of us were

standing on the rudder. At the same time we were trying to maintain altitude.”

The weather outside continued to

worsen.

About that time the No. 2 engine

went out. It would not feather. Pitts called for full power on the remaining

two engines. He called out that he needed help controlling the aircraft.

Co-pilot Lt. Regan “gave all the help he could to the pilot by helping him hold

full right rudder and setting the trim tabs in an effort to keep the airplane

flying straight and level.” It made two complete turns to the left.

The left side of the plane was

silent.

The right side rumbled and screamed

aloud under full power.

Pitts wrote, “I was watching the

flying instruments at the time but I knew No. 2 was out when I felt the plane

lurch.” The left wing lowered. They were fighting to keep their aircraft level.

Pitts lets

us look over his shoulder. “We asked (Fort Worth) for emergency landing fields

and they wanted to know where we were. We couldn’t give our exact location

because we were going around in circles with little fuel left and a 100 foot

ceiling all around.”

They only had

500 gallons of fuel left.

Nilsson

attempted to contact Abilene

by radio, but couldn’t. Regan tells us, “We continued to try to get the Abilene beam. Lt. Nilsson

had tried several times to set the radio but we could only get “jumble”. We

reported this fact to the Fort Worth

radio and asked for instructions but didn’t get any.”

The men

were alone.

The pilot

and copilot were unable to control the plane. They were going down. Air speed

fell to 115 mph. They couldn’t keep a compass heading. Nilsson estimated they

were 50 miles from Fort Worth

with a ceiling no more than 600 – 800 feet.

“I decided

to abandon the airplane,” Nilsson said. He told the engineer to get the crew

into their parachutes and to stand by for his command to jump.

“I pulled

the emergency release and opened the bomb bay doors and dropped the bomb bay

tanks.” The plane had fallen to 6,000 feet.

“Jump!”

Nilsson

signaled Lt. Regan to “tell pilot Lt. Pitts to cut the switch and then jump

through the bomb bay. Lt. Pitts forgot to cut the switch before jumping.”

Nilsson was the last to leave the doomed aircraft.

He floated

down, finally getting below the overcast. He could see the lights of Mineral

Wells off to the north. He hit the ground hard, spraining his ankle and left

foot. “I hobbled to a highway and a car stopped who had already picked up Lt.

Pitts. By this time the Fire Department and the Highway Patrol had arrived. I

gave them the names of the crew so they could be found and picked up. The

airplane crashed three or four hundred yards from where I landed.”

Four miles south of Mineral Wells their

downed B-17F warbird lay aflame in a scrub oak pasture. The Engineering Section

at Patterson Field , Ohio

I’m still reading the report, my

fingers gripping the 68-year-old report a little too hard. “First Lt. Jack A.

Nilsson is to be highly commended for the coolness displayed in this emergency,

and for evacuating his crew in sufficient time to prevent loss of life.”

Regan later

tells that this plane had made a previous trip to Santa Ana where their No 4 engine went out.

They were able to feather it and land at Williams Field. I was thankful this

crew survived their trial in the skies above Mineral Wells.

Researching

this story I began to find that mechanical failures and a “just make it work” mindset

was SOP back then. We were at war. Get in the air. Get in the fight.

2nd Lt.

Pitts later became Lt. General William F. Pitts. He retired in 1975 with a staggering

list of accomplishments including Commander of the Fifteenth Air Force,

Strategic Air Command headquartered at March Air Force Base, CA. Their mixed

force of recon aircraft and bombers, along with missiles, conducted operations across

the Western U.S. and Alaska .

General Pitts was born at March

Field, now March Air Force Base, CA in 1919. He was chief of the Senate Liaison

Office for Secretary of Air Force. He commanded the 327th Air

Division in Taiwan ,

was chief of the Air Force Section of the Military Advisory Group to the

Republic of China, was Commander of Third Air Force, U.S. Air Forces in Europe , stationed in England . He led the Sixth Allied

Tactical Air Force Commander in Turkey .

General Pitts received many decorations and awards.

Back in the final months of WWII,

Pitts went to Tinian

Island Marianas with his squadron where he flew 25 missions

against Japan

as lead crew commander in B-29s. Pitts’ training commander from that Mineral

Wells crash landing Capt. Jack A. Nilsson also flew B-29 missions from the Marianas . Surely the two men saw each other there.

Nilsson’s

crew number 41 plane that night was tagged T46. Its roster included, Capt. Jack

A. Nilsson, Pilot 1st Lt. Adolph C Zastara, Navigator 1st

Lt. Eric Schlecht, Bombardier Capt. Loyd R Turk, Flight Engineer 2nd

Lt. Daniel J Murphy, Radio Operator S/Sgt Eugene P Florio, CFC Gunner T/Sgt Faud

J. Smith, Left Gunner T/Sgt. Robert Starevich, Right Gunner Sgt. Joe McQuade, Radar Operator S/Sgt. Norbert H Springman, and Tail Gunner

S/Sgt. John C. DeVaney.

“All

aircraft bombed the primary target visually with good results.”

Nilsson’s plane came under heavy

fire, crashing during their bombing run against the City of Toukyou on May

24, 19 45Mission

181. His body was never recovered.

One man who

walked out of that 1943 Mineral Wells pasture went on to lead thousands in the

defense of this nation for over four decades, all over the world. Another gave

his life over the skies of Tokyo

6,410 miles west of Palo

Pinto County

Special thanks to O. B. “Butter” Bridier, to the Department of the Air

Force, Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama,

to Richard “Doc” Warner, Civ, USAF 7th Bomb Wing Curator/Historian

(Dyess AFB), Rae Wooten, Michael Manelis, and to

Paul G. Ross, whose father James S. Ross was shot down the same night as Capt.

Nilsson.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

Winter’s Coming to Council Bluff

Winter’s Coming to Council Bluff

This late

in civilization, it’s rare for a seeker to be invited to a place and find most

of the clues just as the People left them. Marker trees are still pointing.

Massive volumes of tips, arrowheads lie about where they fell, though covered

in some cases by the several feet of soil that time has placed atop them.

A location

I’ve begun calling Council Bluffs

is such a place.

In Eastland County

Go figure.

Holding all

of the puzzle pieces the Penetekah Comanches required for their societal

affairs, this quiet chapter setting has been undisturbed by savaging Anglo

collectors.

I’ve waited

many months to write this, to keep Council Bluff’s location safe.

Or maybe

last night, its whispers finally called me back to its mystery.

With winter

finally coming, I hope to go back and let the Native story speak to me, in the

wild, where it happened.

Let truth

have its turn.

Winter’s

coming. The Comanche council fires will burn soon.

Smoke will

clear the trees, and lead me back finally to The People before first snow.

There are Comanche

marker trees, two for sure, two more probably, tips, arrowheads, spearpoints

recovered that range from Penetekah back to Caddo and beyond Clovis . Our friends at Mansker were

wanderers, it turns out.

Caveman

seems crass. Prehistoric peoples.

There’s the high lookout site, along

the ridge, for smokes and surveillance, a place from which a known network node

(Jameson Peak

Below the

lookout there’s a protected valley, walled in on three sides, towering native

pecans along the back-then flowing water way. Several hundred could’ve wintered

here.

We are a 15

minute war horse ride from Old Owl’s main camp.

Maybe

Council Bluff was a retreat, or a camp, before or after our pantaloon-wearing

friend stopped and stayed a little farther to the north. It is chilling,

thinking of the blood-thirsty Comanches, then later Anglos, who surely knew

this place.

What could’ve happened here?

Given the tips, so many, it was a

place for hunters or warriors or men in charge of making life come true for

their people.

We are, if

my information is correct, just up the hill from the old Comanche Road .

It was

later traveled by the Frontier Brigade, that road, though most of it is dim or

lost now, save at the water crossings, or the one not far from this place. The

one Carter Hart found something Spanish, Conquistadors, back beyond our first

Great Depression.

Given the

sheer volume of archeological findings around our feet, we are at a crossroads,

a Troy or Pompeii that held life,

and a story that we long to get to.

I took my

younger daughter that first trip. Our guide was walking ahead, said excitedly,

Come Here. We did. She pointed down. A tip, see the photo, was laying right

where it had long-ago fallen. If we believed in such things, the DNA covering it would’ve been 11,000 years old,

more or less.

I saw that

happen, as did my little girl.

Discovery.

Connection.

Invitation.

I hope I

get invited back.

I’ve

attached some photos.

Winter’s

coming.

Monday, November 10, 2014

The Baby Died, Was Lost, Forgotten, Then Remembered, Taken Back By the Family…Loved, In Heaven and on Earth…You Gotta Read This Slowly, Like Walking, Remembering

We got there as quick as we could. Cold, rainy then windy, then a taste of light sleet coming in from the north.

We’re standing alone, five of us, in a pasture not-enough-miles away from Ranger Camp Valley, from Rattlesnake Mountain’s old wagon trail that led us here.

That ended here.

Forever.

Strangers or family or it doesn’t really matter stand together under a tall swaying sprawling regal pecan tree, bigger around than five full grown men where its trunk meets the too-cold Eastland County sanded black dirt. Leaves fall flutter float into the sad sand muted muddy soil.

The posted letter we received back east was scrawled but specific. That letter kept secret more than it told. “Little Luther’s sick, not good, not good at all. The doctor, he rode two days and one night, out from over near to the Stephensville road.” Doc Evans, or another. We don’t remember. Can’t remember. Not from here. Listen and wait but can’t call the man’s name, riding hard as his horse would travel across that far long ago.

God bless him, whoever he was.

“Please to come to our aid. Our neighbors’ children too sick for them to help. Church closed till whatever this is passes from our community. Fear lives here, sleeping in our cabins, though sleep escapes all but a few. Please to the Lord save our little baby, so sick, crying, come quick, sad we are, our little boy, nothing to do but pray, though Lord forgive me, that didn’t work for the Blackwell’s babe, one place south, one place west. They lost him just before dawn, yesterday morning.”

The letter trails off to nothing, but gets posted. It takes too long, a century till we’re all gathered around the place. Uncomfortable. After all that late frontier family must of gone through, riding down, circling round, trying to figure it all out, what else could we have done? Will they be there when we arrive?

The day before we rode out for Texas, a second scribbled note joined the first. One line, scratched hard into the tattered scrap of paper:

“Little Luther’s gone.”

No signature.

The longest letter I’ve ever read.

This Texas frontier’s scattered with hundreds maybe thousands of lost and forgotten graves. Stories that led into stories that birthed later tales that nurtured and struggled and survived and finally became people or places you yourself probably know about. But we that still walk these woods, pass these places every day, not knowing, not hearing the triumphs and tragedies that came before. Healing us, the silence, or God knows we couldn’t take much more.

Baby Luther Davenport was born then shortly died back in 1901, his family’s log cabin or box-framed home yards from a towering now-invisible native Texas pecan that shades where his family laid their baby to his final rest. One still-here man’s grandmother told Luther’s tale within this man’s hearing when he was a boy, decades ago, and that boy, now that man, never forgot. Though I guess it was Luther’s parents’ tale just as much, back then.

We five, more than five, did indeed go looking for Luther, found him, the family gone, he too quiet but still out there. We did get a posse rounded up and out there finally in person and in spirit, marked his grave, thought deeply of Luther, of the lives of our hard-wrought Texas ancestors lived. We left quietly a little richer, Luther having been born and died beneath this sprawling witness hard-shell pecan. His short story so powerful, so emblematic of where Texas came from.

Leonard and Florence had seven more kids, several of which made it to adulthood then parenthood then into lives out past that brave pecan and out beyond that hard rocky place in that family’s trail to their future. They left their shaking signature in Eastland County, beneath that lonely pecan tree. Then moved north. By the time we finally got to the pasture, they were gone, the old house was gone, the cistern or well or tank or however they got their water was gone. The wind blew, the pecan swayed. Only Luther’s story remained.

Winter clouds gathered.

Luther’s daddy was 33 when the baby died. Luther’s momma 26 when their boy succumbed to the Spanish influenza or smallpox or pneumonia or one from the hundred other diseased predators out running hunting through the woods back then. Leonard and Florence stayed together, but had to have left behind more than most can believe or retrieve from their own life’s story.

All we know for sure is that Luther’s gone. And we’re still here. Though that too is a mystery.

There’s beautiful new carved granite marking Luther’s story now, beneath his pecan, that carved rock the same rich red-pink color as gilds our Texan’s state capital farther south down Austin way. I hope he likes it.

We remember Luther. And hardship. And Texas. How we got here. Pray that we all get past it. This country is still hard. Pray and hope that our children will get to their Promised Land, someday, somehow, walking tall across this hallowed state and hard work and memory and whatever lies beyond.

That ended here.

Forever.

Strangers or family or it doesn’t really matter stand together under a tall swaying sprawling regal pecan tree, bigger around than five full grown men where its trunk meets the too-cold Eastland County sanded black dirt. Leaves fall flutter float into the sad sand muted muddy soil.

The posted letter we received back east was scrawled but specific. That letter kept secret more than it told. “Little Luther’s sick, not good, not good at all. The doctor, he rode two days and one night, out from over near to the Stephensville road.” Doc Evans, or another. We don’t remember. Can’t remember. Not from here. Listen and wait but can’t call the man’s name, riding hard as his horse would travel across that far long ago.

God bless him, whoever he was.

“Please to come to our aid. Our neighbors’ children too sick for them to help. Church closed till whatever this is passes from our community. Fear lives here, sleeping in our cabins, though sleep escapes all but a few. Please to the Lord save our little baby, so sick, crying, come quick, sad we are, our little boy, nothing to do but pray, though Lord forgive me, that didn’t work for the Blackwell’s babe, one place south, one place west. They lost him just before dawn, yesterday morning.”

The letter trails off to nothing, but gets posted. It takes too long, a century till we’re all gathered around the place. Uncomfortable. After all that late frontier family must of gone through, riding down, circling round, trying to figure it all out, what else could we have done? Will they be there when we arrive?

The day before we rode out for Texas, a second scribbled note joined the first. One line, scratched hard into the tattered scrap of paper:

“Little Luther’s gone.”

No signature.

The longest letter I’ve ever read.

This Texas frontier’s scattered with hundreds maybe thousands of lost and forgotten graves. Stories that led into stories that birthed later tales that nurtured and struggled and survived and finally became people or places you yourself probably know about. But we that still walk these woods, pass these places every day, not knowing, not hearing the triumphs and tragedies that came before. Healing us, the silence, or God knows we couldn’t take much more.

Baby Luther Davenport was born then shortly died back in 1901, his family’s log cabin or box-framed home yards from a towering now-invisible native Texas pecan that shades where his family laid their baby to his final rest. One still-here man’s grandmother told Luther’s tale within this man’s hearing when he was a boy, decades ago, and that boy, now that man, never forgot. Though I guess it was Luther’s parents’ tale just as much, back then.

We five, more than five, did indeed go looking for Luther, found him, the family gone, he too quiet but still out there. We did get a posse rounded up and out there finally in person and in spirit, marked his grave, thought deeply of Luther, of the lives of our hard-wrought Texas ancestors lived. We left quietly a little richer, Luther having been born and died beneath this sprawling witness hard-shell pecan. His short story so powerful, so emblematic of where Texas came from.

Leonard and Florence had seven more kids, several of which made it to adulthood then parenthood then into lives out past that brave pecan and out beyond that hard rocky place in that family’s trail to their future. They left their shaking signature in Eastland County, beneath that lonely pecan tree. Then moved north. By the time we finally got to the pasture, they were gone, the old house was gone, the cistern or well or tank or however they got their water was gone. The wind blew, the pecan swayed. Only Luther’s story remained.

Winter clouds gathered.

Luther’s daddy was 33 when the baby died. Luther’s momma 26 when their boy succumbed to the Spanish influenza or smallpox or pneumonia or one from the hundred other diseased predators out running hunting through the woods back then. Leonard and Florence stayed together, but had to have left behind more than most can believe or retrieve from their own life’s story.

All we know for sure is that Luther’s gone. And we’re still here. Though that too is a mystery.

There’s beautiful new carved granite marking Luther’s story now, beneath his pecan, that carved rock the same rich red-pink color as gilds our Texan’s state capital farther south down Austin way. I hope he likes it.

We remember Luther. And hardship. And Texas. How we got here. Pray that we all get past it. This country is still hard. Pray and hope that our children will get to their Promised Land, someday, somehow, walking tall across this hallowed state and hard work and memory and whatever lies beyond.

Luther Davenport

Eastland County, Texas

1901-1901

+

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)