The Lost Road to California

The Future ofAmerica

By Jeff Clark

The Future of

By Jeff Clark

Sometimes stories are bigger than you can grab hold of.

This one's like that. I met eighty-four-year-old Luther Fambro on his place

last Friday. A nice man, wise, gracious.

We talked enough for several stories, spent most of the afternoon riding around. The one tale still rolling around in my head is about the abandoned wagon road he showed me. Let me back up a step.

We talked enough for several stories, spent most of the afternoon riding around. The one tale still rolling around in my head is about the abandoned wagon road he showed me. Let me back up a step.

When I was working on the Alameda story, I ran across a diary that RIP (“Rest

in Peace”) Ford wrote as he rode through this part of Texas around 1835. He turned his reins

north, then all of the sudden took off west. Went up a valley to avoid high

mountains, arrived at level land on top, then continued toward the sunset.

I've always suspected he went up Bear Creek Canyon Eastland County Palo

Pinto County

The mystery wagon road leading up the canyon has long since

been abandoned. A series of massive bridge headwalls of stacked native stone,

save one of reinforced concrete. Huge eight by eight timbers, preserved like

they were cut yesterday, like those used during Hogtown’s oil boom lie in the

brush. Smaller boards I take to be the old deck of each bridge hide here and

there. This old road crosses Bear Creek seven times in three miles.

Back before water wells, stock tanks, oil exploration and

other man-driven alterations to area groundwater, the streams and springs often

flowed year-round. The erosion from now-dry springs and rivulets is still

carved into the sides of this beautiful valley.

As we ascended the valley shadowing this old road, I was

struck by the gentleness of its grade, far less steep than modern-day I-20. A

wagon and team could have made it up this valley. There would have been places

to camp, small pastures to graze tired teams, forests (then) of oaks, now

crowded by cedar and mesquite. Abundant cover and water would have fed

dinnertime game.

We pass where remnants of a whiskey still were broken apart,

probably by “revenuers” (revenue agents), I presume during Prohibition. Copper

tubing and sundry components were strewn all over the ground, now long-since

vanished. The still was hidden about twenty yards off this road.

My 1917 Soil Study map for Eastland County

As we ascended this lost wagon trail, I couldn't help but

wonder if my Russell Creek Community friends from the 1870s had ridden their

horses, had driven their teams up this route. Russell Creek

After returning home, I checked with some friends who I

thought might remember the wagon road, might be able to tell me if this was the

road to California .

Highway 80 was commissioned in 1926. It surely replaced this road. Folks around

Ranger told me that a traveler would have taken a northern route to Caddo, then

east toward Fort Worth .

The hardier could have gone down the more exciting narrow path along the T

& P rail bed, descending (like a rock in some places) the perilous wilds of

Wiles Canyon

This land could have been made "off limits" by

some long-ago six-shooter-toting landowner, arresting public use of this road.

Ornery first and second generation ranchers ran cattle up and around this stretch

of country back then.

I would’ve written the road off as a neglected old wagon

trail, common in this part of Texas, but for the "established",

engineered look of these bridge headwalls, some wider than twenty feet. A lot

of trouble went into building this road. The path had to have been a major

east-to-west-route, at some time, for some major reason.

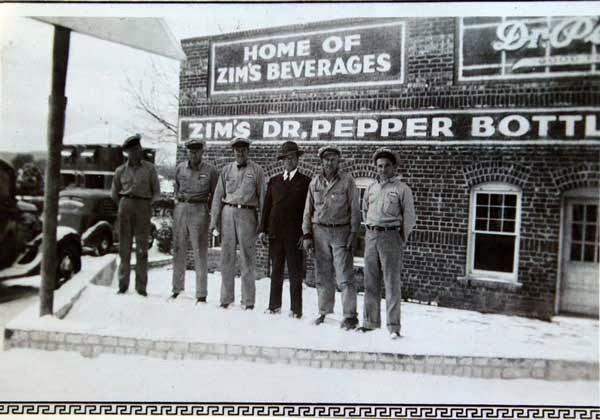

I've included a couple of photos, in case anyone remembers.

I suspect my storytellers from that time have passed on. Why does any of this

matter? Old wagon roads knitted this country's west-moving settlement into a

young nation. This dusty road undoubtedly carried daily trips up to Russell Creek Church of Christ

The T & P had laid the train spur’s track for the next

coal mine here, had built the lake, built fourteen houses, according to 1917’s

map. But as they were about to sink a shaft, Ranger's star-crossed oil boom

hit. The coal mine never got dug.

Could this have been one road to California ? Could this now-abandoned path

have carried the dreams of a much-braver nation to its far coast, birthing

settlement along the way? What picturesque characters might have slid up the

road slicing these two mountains, from 1835 to as late as the 1920s?

Topography would have almost forced one to take this route.

Did the Caddo peoples, the Comanches, the earlier wandering Natives whose tribe

names have been lost walk this path? Surrounded for miles by steep mountains and

cliffs, it is almost certain.

Mr. Fambro's dad was Truman Conner ("T.C.")

Fambro, who lived for a time up around Wayland, north of Ranger in Stephens County Bear Mountain . The

communities of Marston and Mountain had vanished by then. Gourdneck and Tanner

were sinking fast.

Some thought his land purchases ($16 - $22/acre) were

outrageously over-priced, ill-advised. That was before Highway 16, or I-20.

Before land was bought for "leisure”. Ranch land had to cash flow, back

then.

Luther Fambro moved back on the family place about 35 years

ago. While in high school he worked for Mr. McKerrin in Breckenridge, at a

men's clothing store. McKerrin was good to him. Young Luther'd work at the

store first period, then after school and on Saturdays (after a tough Friday

night football game).

He played "end", there being no tight ends or

wide receivers back then. World War II called him away for three years, going

here and there as some commanding officer thought fit. When he returned, he

ended up at North Texas in Denton on a full scholarship, aided also by

the GI bill. Fambro's loyalties to the school are evident, a bright green North Texas flag greeting you as you enter his spread.

Remember, I grew up in the city. Still, some parts of rural

economics don't make sense to me. I asked Mr. Fambro how a person could make

modern $2,000 per acre land prices work, running cattle or maybe farming. I

can't even almost make the math work. If a deep-pocketed person buys land for

recreation, pays cash as an investment, then the numbers can work, after a tax-code-twisted

fashion. Tax-free exchanges, deferred loss and well, all that wealth's got to

go somewhere.

This tough land can prudently support one cow every twenty

acres. $40,000 of land, for one cow. Doesn't paying more than a few-hundred-dollars

per acre doom one's ranching enterprise? How do couples starting out, wanting

to farm or ranch get going? They'd have to inherit an operation, earn a great

income from some paycheck job, or borrow the mother-of-all land loans. Even

then it might not be enough.

Mr. Fambro has worked hard his whole life. Shared that he

wasn't always what he called "well off". He had a stroke in 1992,

making it tough to work his land, and the thousands of ranching acres he'd

leased to add to the mix. Still, his hard work seems to have paid off.

His place doesn't boast one of the gleaming monster homes

springing up in this part of rural Texas, perhaps, but he's living on ancestral

land, some family nearby, happy, secure in the strong beliefs that brought him

here. We drove though gates, passed different breeds of cattle. He counted

them, “took them in” through his front windshield. He's still working this

land. The man helps out some groups he's fond of, attached to, out in the world.

He's "seeing to" the places he came from, as my granddad would’ve

said.

Turns out Fambro lived in Richardson once, north of Dallas, a couple of

blocks from the high school I graduated from. He coached at powerhouse Highland

Park, who my Richardson

School Highland Park , if we lost by 14 points or

less.

I'm staring in frustration at my notes from Mr. Fambro's

kind visit. There are ten more stories in there, easy. I will share more, as

this tale continues to unspool. That old road has gotten under my skin. Like

our country, too many have forgotten where this wagon road came from, and most

don’t have a clue where it’s going. But we know by looking at this old road,

that once, whatever rolled along its path was significant.

I hope things are good with you.

No comments:

Post a Comment