Soda Pop Offer Tints

Louis White’s Memory

By Jeff Clark

“Life was cheap back then.”

Butter

Bridier is 85. He spent his first decade of life in coal mining Thurber. The

Bridiers lived in House 1269. That’s eight-year-old Butter in the photo telling

this story.

“One day Louis White knocked on our

front door. I didn’t even know his name.” Louis was 14. After knocking, Louis

stepped back off the Bridiers’ porch. He was black. Times were different.

“He wore no shirt or shoes, his hands

in his pockets.”

“Miss Polly Boo,” Louis said to Butter’s mom, “Charlie

said I could ride old Mary.” Charlie is Butter’s older brother.

“Are you sure Charlie said you

could ride his donkey?”

“Yes m’am. If he hadn’t, I wouldn’t

be here.”

Butter’s dad was French, his Polly

Boo nickname derived from “Parlez vous Francais. Louis gets the donkey bridled.

He dives halfway across her back so he can straddle her to ride. But when Louis

jumped, his pants slipped down around his ankles. “My mom laughed so hard snuff

ran down her face.”

Another time Butter and his mom

drove their A model Ford to Thurber’s service station for two gallons of gas. “That

was all you could afford, even at 15 cents a gallon.” Louis is there, leaning

against an iced soft drink cooler.

“Hey Louis.”

Louis looked at Butter, not lifting

up from the cooler box. “You want a soda pop?” he asked Butter.

“I don’t have any money.”

“I’ll buy you one. I got money.”

“You won’t pay for it.” Butter

doesn’t know if Louis had a nickel, dime or what. Grown people in Thurber didn’t

have 10 cents in their pockets back then.

“I don’t remember seeing Louis alive

after that.”

The White

family is living with Louis and Isabella Walters inside House 208, according to

the 1920 census. A 40-year-old “Louis” Walter and a four-month-old “Louis”

White. Father Ed White is 65 and wife Lucy’s 37. By 1930, Louis is 11, his

father 75, mom Lucy 49. They’re living in House 102, in “Colored Town

The census shows the most money any

of 50 names on the page possessed was $20 (all races). Ed and Lucy had “none”.

Though Thurber had no black school, Louis was able to read and write.

Thurber’s Little Lake still sits

just west of New York Hill. You could swim or fish there. There was a homemade

flat-bottom row boat anyone could use, made of 1 x 12’s, tar and pitch keeping water

out. Two boys about 16 joined Louis in the boat that day.

He could’ve fallen overboard

accidentally. His shipmates could’ve wanted to see if Louis really couldn’t swim.

Louis disappeared beneath the surface.

Johnny Elwood brought his metal

boat. He and Ted Botts went back and forth looking for Louis’ body with a

grappling hook. Fifteen to twenty people watched from shore.

“I came around our house the day of

the drowning. Diagonal across the street Miss Crane had a grandson Charles

Sanders, playing with a yo-yo. “Hey Butter, you know N___ Lewis drowned?” He

just kept yo-yo’ing. “I told momma and she hurried to Little Lake to see.”

When Louis was brought to shore, he

wore no shirt or shoes. A stretcher carried him up on the dam. He’d been in the

water over an hour. No effort was made to resuscitate.

“Dr. Baldridge was standing by

Louis’ feet. He said, ‘I pronounce him dead.” The crowd dispersed.

There wasn’t

an inquest, it doesn’t appear. The family cared, perhaps few others. “It was

hard to stay alive back then.” Louis was buried in an unmarked grave in Thurber Cemetery

Blacks had church below New York

Hill. Though all races mined together, there was little associating around

town.

There was a

black preacher once, preaching real loud. “I got scared and started crying,”

Butter told me. “They once passed the plate. One guy didn’t pay the plate any

mind as it went past. The preacher asked, “How ‘bout you sir? You got something

you can give to the Lord?”

“Yeah, I might give Him a dollar.”

“Very good, put it in the plate

there.”

“Well, if you don’t mind, I’ll give

it to Him when I see Him.”

Louis White

was willing to share a soda, Butter told me these 76 years later. “I always

remembered that.”

Louis’

mother Lucy died two months later to the day of a broken heart. We don’t know

if his then 79-year-old father had died or moved away. Lucy was getting up in

age, in bad health, poorly fed, facing the world’s worries without that

14-year-old boy’s smile to keep her going.

“Those were survival times. As bad

as it was, Louis offered to buy me a soda pop.”

When the restoration of Thurber Cemetery

After he retired, he talked to Flogene

Boston who lived on Park Row. She told him, yes, she went to Louis’ funeral.

His grave’s right there by the fence. The Bridiers found two plots that “fit”

her memory.

Butter and wife Faye gave Louis his

tombstone. Leo Bielinski gave Lucy hers.

“I can always remember that little

guy,” Butter told me, “leaning against the soda cooler. If I could put flowers

on only one grave at Thurber, it would be his.”

Lucy White’s headstone reads “A

Mother Grieves No More.”

Little Louis White drowned, after

teaching one important lesson.

“You want a

soda pop?”

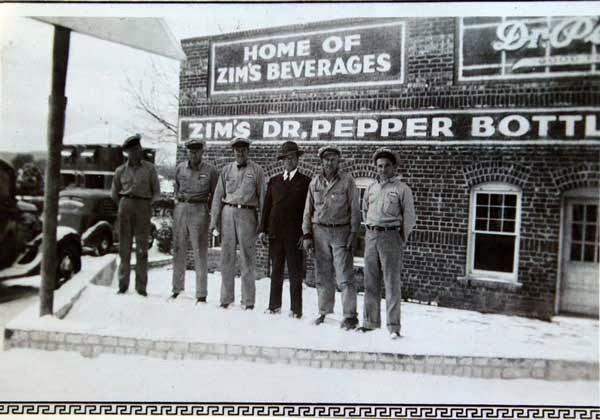

SUGGESTED CAPTIONS

1. The story

teller, eight-year-old Butter Bridier in front of House 1269 in Thurber.

2. The

grappling hook used to find Louis White’s body in Little Lake.

3. Mother and

son’s headstones.

No comments:

Post a Comment